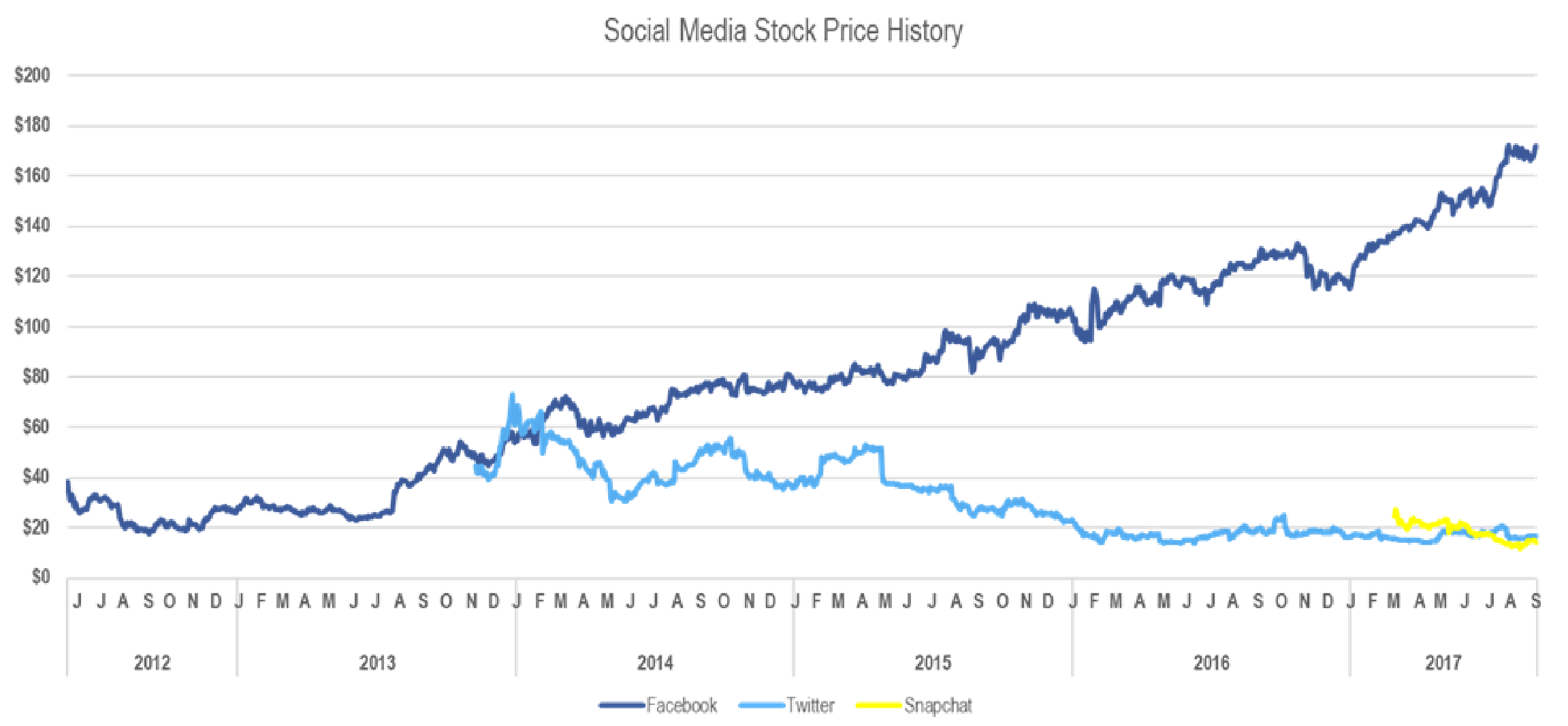

On March 7th of 2017, Snapchat stepped into vast unknown of the equity markets, issuing over 200 million shares at $17 a share in its initial public offering. By the end of that day, Snap Inc.’s share price was trading at over $24 a share, putting the company’s valuation at $33 billion. Social Media companies are used to receiving love and attention on their opening days, as Twitter gained over 72 percent on its opening day and LinkedIn more than doubled its share price in its own debut. Facebook is an outlier, in that the market seemed to believe that the company’s valuation was appropriate. On the first day of trading, Facebook’s shares rose less than 1 percent.

But inevitably, the expectations investors place on these select companies and the ability of these companies to deliver on those expectations bring the stock prices down below these lofty figures. Two years after Twitter doubled its stock price on its very first day, the stock price fell below the $16 threshold that the stock started at. LinkedIn’s share price struggled before being purchased by Microsoft. Facebook, with its less glowing debut, is the stock that has in fact seen upward growth since its inception, though it too struggled to gain traction in its opening months of trading.

Underlying the volatility in the social media sphere, is the difficulty in pricing stocks with no positive earnings. Coming up with the appropriate stock price for Twitter, which had never had a positive quarter of earnings before listing its IPO, is difficult in that the classic valuation methods are not entirely helpful, or at least not helpful at generating large valuations. Wall Street prices stocks with several goals in mind. The first is to generate as much capital as they can on the shares being offered for the company doing the issuing. This in turn accomplishes the more obvious goal of generating as much revenue for the underwriter as possible, as underwriters usually take a fee as a percentage of the offering. The larger the offering, the larger the fee the bank will receive. In Snapchat’s case, several major banks underwrote the deal, with Morgan Stanley taking the lead. The bank received 30.2 percent of the shares that were underwritten and generated a fee of over $25 million. Goldman Sachs received over $21 million for its own work on the deal. Lastly, the underwriter attempts to ensure that the offering price is within the market’s expectations. The goal is to generally attempt to see a moderate rise in the stock price on the opening day, so that early purchasers of the stock feel rewarded for the risk, and the company doing the offering doesn’t feel that money was left on the table. However, the appetite of the market on any given day for any given stock is difficult to predict.

In valuing social media companies, Wall Street has gotten increasingly creative in justifying the valuations they generate, removing themselves from finance fundamentals in exchange for alternative valuation methods. For example, they value these companies based on daily active users, time on site, average revenue per user and others as a way of measuring user engagement with a certain app or website.

To understand this thinking, one must understand how companies like Twitter and Snapchat make money. They make money primarily through advertising. Therefore, apps that have more users and who have users that spend more time on those apps would theoretically be more competitive for advertising dollars and capable of charging higher rates for ads. At its most basic level, Snapchat currently has 173 million people using its app every day. For advertisers, that is 173 million people on any given day that they can reach. But the sheer number of users is not the only reason social media can attract ad dollars. These sites are perfect for native advertising which are ads that blend into the app, making it look almost like a post instead of a traditional pop-up ad. Native advertising is generally more effective at generating clicks as pop-ups are just supremely annoying and ads on the top or sides of a website are generally not the focus of user attention.

Yet there is one additional element that made the industry innovative to begin with. To maximize the effectiveness of advertising by reaching the audiences that would be most susceptible to the product or ad in question, you need information. Information that was generally hard to collect before the advent of social media. Companies looking to advertise may know the demographics that their product is geared for, but how do you most effectively make sure that your ad runs to those people? Social media provided incredible access to this information, but even more importantly, people gave up this information willingly. Even more than just age and gender, people were listing what they are interested in, what they enjoy doing, where they live, where they are, what their political affiliations are, and even their relationship status. This information is everything a company would need to target the groups most likely to respond to their products and marketing.

While this ability to get people to offer valuable information about themselves was innovative, the ability for these companies to continue to innovate past this point has been questionable. While platforms and functionality have improved, the competition for people’s time and attention has escalated as new social media companies with their own niches and offerings have begun to crowd the market. In recent years, an incestuous process of simply incorporating the features of these other products has taken the place for true innovation. Facebook’s purchase of Instagram was a move out of self-preservation as Instagram has effectively turned Facebook into the doldrums of inane political posts and birthday reminders. Instagram’s greatest achievement since has been to copy Snapchat’s story feature and then on top of that add filters. Who has filters? Oh yeah, Snapchat.

In Facebook’s bid to stay relevant in the face of burgeoning competition, Snapchat garnered a reputation for innovation. However, the “innovation” that Snapchat has brought has not been monetizable to this point because Snapchat collects a less diverse range of information. The unique element of Snapchat is that it has information about where people are and what they are doing right now. On Facebook, you might post a picture you took a week ago. With Instagram, it may be more current but there is no guarantee that pictures that are posted are indicative of a person’s current location and activity. Snapchat offered the potential to reach consumers in the moment. When you post a picture to Snapchat, that picture indicates what you are doing and where you are at the exact moment you were using the app[i]. In addition, Snapchat was different in that it was geared to be more of a communication device (or sexting device) than it was supposed to be a repository of information about one’s person. The fact that snapchats and stories disappeared meant that there was less pressure to make every picture or post perfect and it could be used as simple fun. It had no repercussions. You could snap anything and everything and it would be gone.

While the initial idea of Snapchat was in some ways innovative, Snapchat has managed to ride by on that reputation, offering little in recent years. Let’s look at the major product improvements Snapchat has offered. In 2013 Snapchat added stories which allow users to share a moment with all their Snapchat connections for 24 hours. In 2015, Snapchat launched “discover”. While this is perhaps the biggest move forward for generating ad dollars, most Snapchat users will know this feature because this is where you go for sleazy celebrity gossip if you are unwilling to pick up a copy of People magazine while waiting in line at the grocery store. In 2015 the company launched “lenses” which are the filters that millions of teenage girls love because you can give yourself virtual dog ears and a long flappy tongue. Which I should probably be more thankful for because I’ve seen a rather sudden decrease in the duck face.

Most recently in 2016, Snapchat released its spectacles to open new avenues for revenue generation by entering the retail space. The spectacles are the glasses that solve the critical problem of people wanting to stay connected to social media while not having to stare at their phones. As unique as the problem is that Snapchat was trying to solve, the rollout for the device as even more unique. The company at first only offered the glasses from select vending machines and one dedicated pop up store in New York. The vending machines, called Snapbots, never stayed in one place for more than a day. While the glasses were generally well reviewed, no one had them and finding them was incredibly difficult (originally the company’s intention) which doesn’t sound like a terribly sound product strategy unless you are trying to market your item as a luxury good. At the $130 price point, it maybe was as I can get a pair of Ray-Bans for that price. The company has since rolled out the product on several online retail platforms and has even moved into brick and mortar (seriously it’s like Snapchat is the only tech company trying to move into brick and mortar and not get out of it). But underneath the surface of the gadgetry is that Snapchat is offering a $130 way to use a product that for the past five years people have been using for free. Perhaps the effort was admirable but within a half of year of launch, Snapchat reported slowing sales for the glasses along with news that it’s daily active user count fell 2 million users below Wall Street expectations. While I don’t particularly care for Wall Street expectations, the revelation indicated that Snapchat was experiencing headwinds as its competitors were continually pilfering their ideas.

But this leads to an interesting question. How innovative is a company, if its innovations are immediately and easily duplicated by its competition? Instagram’s addition of stories opened a new avenue for its users (many of which likely also have a Snapchat account) to post frivolous everyday occurrences without the need to try to garner likes. Instagram offered a judgement free avenue for all those photos that may not be “insta-worthy” and then added its own versions of snap-like filters. At this stage, the most innovative thing Snapchat brings to the table is a dancing hotdog. But this is a question of innovative relativism. It asks, how innovative is Snapchat relative to those it competes with. Objectively, how innovative is Snapchat? While I do not have insight into how difficult it was to create the technology that makes Snapchat possible, difficulty does not presume necessity. Would the world be a truly terrible place without an augmented reality featuring a dancing hotdog? How would we ever get by without dog ears and massive rose-colored glasses? The underlying identity of Snapchat and its ability to function in a gray area between text messaging device and photo album makes Snapchat unique. But its attempts to further leverage that idea have fallen short of truly making communication better, faster, or easier.

But as far as financials, companies don’t necessarily need to be innovative to be good investments. You wouldn’t particularly think of a utility company as innovative, though they certainly could be and they certainly can be good investments. The main problem Snapchat faces, is that it can’t monetize the upgrades in its user experience. Snapchat collects a less diverse array of information on its users than a Facebook or Instagram. Aside from your name and your location, what else can Snapchat really track? They don’t expressly have access to your interests or your viewing habits outside of the discovery features that you click on. Advertisers cannot actively target certain individuals to maximize their response rates on their ad dollars. With Snapchat, they know that there are a lot of people using it, that the users are relatively active, and that it is generally a young audience. They know where those individuals might be located at any given moment but without the context of knowing where you shop or what you do, how do you truly maximize the effectiveness of the information Snapchat commands? And so as much as Snapchat invests in boosting its user experience and offering more reasons to come back and use the app, unless it finds ways to get users to offer more information about themselves, advertising to Snapchat’s users may not be as efficient or offer the same return per user as Facestagram.

Additionally, if a user has a Facebook, an Instagram, and a Snapchat than an advertiser could reach said user through any venue they want. For example, I have all three apps. Of the three, I use Snapchat the least. I am the guy on Snapchat who never posts anything but totally spies on people’s stories and occasionally throws out a congrats message. I post to Instagram once a day and I generally post photography with photography hashtags. So Instagram now knows that I like photography. And coincidentally, all the native advertising I experience is for Canon and Nikon. I use Facebook pretty much the same way as I use Snapchat but with the occasional like and maybe a profile picture change so everyone knows my hair is receding. But I’ve filled out where I live, what my movies and interests are, and once again the advertising I experience is generally connected to the information I have displayed. With snapchat, the advertising I see has frankly nothing to do with anything I might be interested in. I get ads for horror games when I’ve never even seen a horror movie let alone been willing to engross myself in whatever Resident Evil we are on now.

While Snapchat has certainly tried to diversify its revenue model away from simply advertising, the future of Snapchat’s financial success revolves around making the users it currently has more valuable to both the company and to the people who would wish to access that userbase. Snapchat’s focus has been on keeping the app feeling new and continually investing in new features. However, if these features are necessary to keep people interested and engaged in the app, then this model seems unsustainable and nowhere near as scalable as initial investors seemed to believe. Morgan Stanley, the lead underwriters on Snapchat’s IPO, originally placed a price target of $28 for Snapchat’s stock price. Now that target stands at $16 a share and Morgan Stanley’s reasoning was tied to the reality that Snapchat had been unable to improve its ad product and user monetization. As a general rule, I put little stock in Wall Street estimates. But when a company who underwrote a stock says the stock is worth less than what they sold it for, that isn’t exactly a glowing endorsement of the future prospects of the company. I believe that there is room on everyone’s phones for Snapchat. But as far as the public markets, it seems to me that Snapchat’s best prospect is with another company. Snapchat on its own will likely struggle at the mercy of investor expectations and desires, but could offer access to an audience that many large media companies are not well equipped to engage.

In theory, there is a stock price for Snapchat that would make this company an intriguing investment. However, given how murky the valuing of social media companies can be, I don’t have any way of saying if Snapchat’s current stock price is approaching that level. Social media stocks are a group that I’ve stayed well away from in my personal investments and Snapchat is a stock that I will be staying even further away from. Ultimately when you purchase a stock, you are purchasing a piece of a company’s earnings going forward into the future. Snapchat doesn’t have earnings and it hasn’t provided a credible plan to achieve earnings in its short time as a publicly traded company. As long as the market continues to build valuations off of metrics like revenue per active user, where revenue is not what investors end up seeing as either dividends or reinvestment, then it would seem that investors will continue to fall prey to valuations that are reflections of market zeitgeist and not market fundamentals.

[i] However, it should be mentioned that Snapchat broke this mold by allowing users to share “memories” or old photographs they have taken outside the app with their phone’s camera feature. You know…like Instagram.